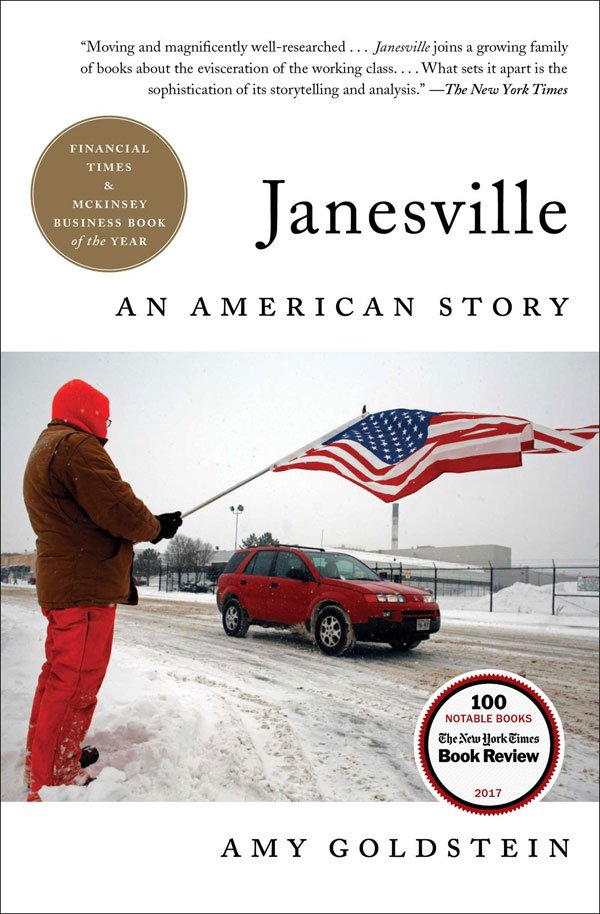

Janesville, An American Story by Amy Goldstein

Recommendation

Pulitzer Prize–winning Washington Post journalist Amy Goldstein earned wide recognition for this important entry in a new, sad American genre: stories of loss among the manufacturing middle-class. When General Motors closed its Janesville, Wisconsin, assembly plant in late 2008, the loss nearly ripped the town apart. Writing with grace and skill, Goldstein combines empathy with objectivity in her coverage of the eight years following the closure. She tells the story largely from the perspective of a dozen or so real people who stand in for thousands of others who suffered, sometimes triumphed and occasionally died. Most of those whom the layoff affected have less today than in 2008: less income, less security, perhaps less hope. But they gained inspiration from their community, their neighbors and themselves as they learned that Janesville and its people share unique generosity, resilience and self-reliance. Anyone interested in economic, social and political trends will devour this book.

Take-Aways

- In 2008, after 85 years, General Motors (GM) laid off thousands of workers and closed its oldest operating assembly plant, which was in Janesville, Wisconsin.

- The campaign to persuade GM to keep the plant open failed, despite the efforts of former Wisconsin governor Jim Doyle, former congressman Paul Ryan, state and local officials, and the union – including more than $400 million in enticements.

- The plant stayed closed. Its economic base lost, Janesville has struggled to recover.

- Middle-class former “GMers” fell out of the middle class.

- Some working-class low-wage earners fell into poverty and even into alcoholism, drug abuse and homelessness.

- For a time, the town’s foreclosures, bankruptcies and suicides spiked.

- Federal government retraining grants helped some laid-off workers find new jobs, but not all.

- For most people, salvation came through their own efforts and the work of heroic community leaders and volunteers.

- Despite low unemployment today, most people in Janesville are living with less income and security.

- Some people emerged from the ordeal with new faith in their community, their neighbors and their own grit.

Janesville Book Summary

“GM Janesville”

Automaker General Motors (GM) arrived in Janesville, Wisconsin in 1919. When GM’s original operation – producing tractors – failed in 1921, the company started making trucks and cars. The plant closed for a year during the Great Depression and made munitions during World War II. Otherwise, the local GM operation made cars, trucks and SUVs for more than eight decades. The plant became a path to the American Dream for generations of families, a central part of Janesville’s identity and culture.

The Rupture

On December 23, 2008, GM Janesville, the automaker’s oldest plant, shut down. The Lear Corporation, its supplier of car seats, closed, too. As a result, just as the worst US economic recession in 70 years began, 9,000 people lost their jobs. Janesville laborers had prided themselves on being among the nation’s most loyal and their union nurtured good relations with management. When GM announced the closing in June, 2008, it gave the plant two years to wind down. The delay and the expectation that the plant would reopen – as it had in the past – gave most people hope. Many retained their faith in GM, including Marv Wopat, who worked for 40 years at the plant and retired just before it closed. His son Matt was among the first to lose his job.

Leaders React

Wisconsin governor Jim Doyle (2003–2011) and Janesville’s powerful then-congressman Paul Ryan remained hopeful. In mid-September 2008, they led a delegation to Detroit to save the plant. They presented a well-rehearsed proposal with incentives for GM to keep the plant open. Yet only a month later, GM announced it would close the plant in two months rather than two years. Meanwhile, the United States and global economies plunged into a free fall.

“When Jerad Whiteaker “was laid off from GM, he and Tammy had about $5,000 in savings. After more than one and a half years of pulling out a bit at a time to keep up…the savings are gone.”

Community leaders like Bob Borremans, head of the Janesville job retraining center, and Mary Willmer, president of Janesville’s largest bank, sprang into action. Borremans believed federal aid money for retraining might lead to better, more fulfilling work than GM had available and could bring diversification and strength to Janesville’s economy. Willmer saw an opportunity to knit Janesville and surrounding towns in Rock County closer together.

“Keeping up appearances, trying to hide the…pain…is one thing that happens when good jobs go away and middle-class people tumble out of the middle class.”

Mass layoffs at an anchor employer like GM create a ripple of consequences. With the loss of thousands of well-paid jobs, workers stop spending and other businesses had to let employees go. Willmer formed the Rock County 5.0 economic development initiative with local billionaire Diane Hendricks. They sought to link Janesville and the neighboring city of Beloit to attract new businesses.

“While factory jobs have been appearing lately in some parts of the United States, Rock County is not one of those places.”

Marv Wopat, though secure with his GM pension, fought to reopen the plant. He convinced cash-strapped county leaders to put together an enticement package worth $20 million, hoping to convince GM to choose Janesville as the site to build its next-generation subcompact vehicle. The county’s $20 million combined with $115 million in state financial incentives, $17 million from the Janesville and Beloit city governments, and $213 million in additional concessions from the local United Auto Workers (UAW) union. In all, Janesville offered more than $400 million in enticements to GM, but even that proved to be inadequate. Orion, Michigan, won the plant with a bid almost five times larger – the largest up to that point in US history. Orion agreed to let GM pay new employees – and many previously laid-off workers – $14 per hour, half the old rate. Much of the work would go overseas with parts shipped back to Orion – a Pyrrhic victory emblematic of the new US auto manufacturing industry.

Harsh Reality

During the aftermath of the 2008 recession, the US government rescued GM and other firms from bankruptcy, but no relief arrived for Janesville. Despite pleas from Ryan, Willmer and other leaders to forget GM, many former employees – “GMers” – had intertwined their identities and hopes with the manufacturer.

“Now the GMers – plant managers and workers alike – are gone.”

Mike and Barb Vaughn were among those who confronted the future head on. Barb used federal retraining assistance to study for an associate degree in criminal justice. Mike retrained for a management job by pursuing a degree in human resources paid for by government assistance, breaking from three generations of union men. Going back to school wasn’t easy, even if the government paid for it. As Mike, Barb, her friend Kristi Beyer, Wopat and others chose retraining, they faced a year or longer without income while preparing for jobs that might not materialize. Many had kids at home and mortgages to pay. As the recession ground on through 2009, bankruptcies and foreclosures spiked across Janesville and Rock County. Willmer convinced local bankers to offer relief to workers who couldn’t afford their mortgages. But no respite came for people with mortgages from national lenders. Janesville’s decades-long tradition of food and toy drives at Christmas ended in 2009 for lack of donations.

“Training people out of unemployment is a big, popular idea. In fact, it may be the only economic idea on which Republicans such as Paul Ryan and Democrats such as President Obama agree.”

In early 2010, another Janesville institution, the Parker Pen factory, began closing to move to Mexico. Another 153 people with good jobs became unemployed. Almost two years after his layoff, GM offered Wopat a job in Indiana, more than four hours away. With Janesville home sales nonexistent, his mortgage underwater, his kids in school and relatives nearby, the Wopat family decided not to move. Matt began leaving his family for five days a week and commuting home on weekends. He felt he had no choice. His retraining wasn’t likely to land him GM’s $28 per hour plus benefits and retirement.

“Even when people desperate for a job try to retrain, as the Job Center has been encouraging, they don’t always succeed.”

Others – like Jerad and Tammy Whiteaker – chose family over GM’s offers to relocate. For $4,000 in severance and six months extended health insurance, Jerad left GM. He accepted a local job at less than half his previous salary. Tammy took part-time work as a substitute teacher, and their twin daughters, then 13, started waitressing. They almost couldn’t keep up with their mortgage. They sold many of their belongings and slashed their budget, including groceries, by 75%. A few months later, GM offered laid-off workers the choice to move to a plant 1,000 miles away in Ohio or to leave GM with nothing at all.

“As middle-class families have been tumbling downhill, working-class families have been tumbling into poverty.”

Those in retraining programs began to graduate. Some – like Barb Vaughn and Kristi Beyer who earned associate degrees in criminal justice – found work. Both landed state jobs in the local jail. The local newspaper ran a front-page success story about Kristi, who graduated at the head of her class.

Frustrations

Through 2010, as more Janesville workers fell from the middle class, Scott Walker (incumbent since 2011), a politically conservative firebrand, became the Republican candidate for Wisconsin governor. His promise of jobs attracted the state’s disenfranchised, including long-time Democrats, to vote for him. Bank president, Mary Willmer, a Republican, urged people to talk about Janesville in an upbeat way. She became the town’s voice of optimism. Few shared her hope and, as the years wore on, former GMers took any work they could get, sometimes displacing working-class people in minimum-wage jobs.

“The food pantry “is so strapped that it is limiting food these days to the first 40 people in line…and only if you haven’t been there in at least a month.”

As this happened, more of Janesville’s working poor lost their grip on normalcy. Some turned to drugs and alcohol. Families came apart, and kids start appearing on the town’s streets – homeless. The community rose to help. Ann Forbeck, who had five kids of her own, started what would turn out to be a long-term effort to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for teen homeless shelters. When newly impoverished kids were in school, the federal lunch program helped them. The community organized the Bags of Hope Christmas food drive, giving groceries to the Janesville families most in need. The initiative started in the school system in the hope that students wouldn’t go hungry over Christmas.

“Barb Vaughn “believes that Lear’s closing was the best thing that could have happened. Its closing taught her that she is a survivor. It taught her that work exists that is worth doing, not for the wages, but because you feel good doing it.”

At the turn of the new year in 2011, Willmer felt confident in Janesville’s future, despite the previous two terrible years. Barb Vaughn quit her job as a jail guard after discovering her passion for learning and her desire to help people stay out of jail. She returned to school full-time to pursue a bachelor degree in social work.

“Look for the truth of the situation…and embrace it.”

As protests mounted against Walker’s arch-conservative anti-union reforms, some in Janesville turned against public servants like teachers, who became targets of the resentment and anger of the unemployed. In effect, “two Janesvilles” formed: the prosperous versus the poor and Democrats versus Republicans – including some Democrats who switched allegiances and believed that fewer worker rights might lead to more jobs.

“Union or not union, no job is forever. No guarantees.”

To keep his family in the middle class, Wopat continued his exile in Indiana. Mike Vaughn, after years of work to earn a degree in HR management, found work but for only half what he earned before – plus he had to work nights. Janesville graduates of retraining programs suffered higher unemployment and lower wages on average than GMers who decided not to retrain and looked for other work instead.

“Nearly six in ten people think that Rock County will never again be a place in which workers feel secure in their jobs or in which good jobs…are available.”

Kayzia Whiteaker, whose dad Jerad had found work as a jail guard, felt grateful when her teacher offered her access to the school’s “Parker Closet” of donated clothes, food and sundries. The Whiteakers’ problems worsened in 2011. Jerad hated his new job, which, even with overtime, didn’t cover his family’s needs. Kayzia and Alyssa, now 16, worked more hours. They paid for groceries out of their bank accounts, which were healthier than those of their parents.

A Slowly Changing Tide

In early 2012, several start-up biotech firms chose Rock County for their operations. One company wanted $9 million in land grants, infrastructure investment and tax relief from Janesville even before it proved its business model or found a market for its product. Its jobs would rival GM’s in pay, but the biotech expected to hire only about 150 workers over three years. The Janesville Council approved the enticements, despite its limited $42 million annual budget. On June 5, 2012, Walker survived a recall vote, remaining the state’s governor even though fewer than 30,000 of the 250,000 new jobs he’d promised 18 months earlier had materialized.

“With broad outside forces…unable to lift back up its once prosperous middle-class, Janesville has been left to rely…on its own resources.”

Kristi Beyer suffered when her son came home from Iraq with PTSD. With her marriage in trouble, Beyer brought drugs to a prisoner. They had an affair, he blackmailed her and the sheriff suspended her. Two days into her suspension, Beyer killed herself.

In August, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney named Janesville native son Paul Ryan as his running mate. The Romney–Ryan campaign staged Ryan’s “homecoming rally” outside Janesville. By election time, Kayzia and Alyssa were 18 and could vote. Like 60% of Janesville voters, they rejected Ryan and Romney. Ryan lost Janesville and barely kept his congressional seat.

“They haven’t forsaken the old can-do.”

After Jerad Whiteaker lost his job, Kayzia and Alyssa each worked two or three part-time jobs to help. They received Bags of Hope at Christmas for the third year running. In 2013, the state granted them $160 a month in grocery assistance. When the University of Wisconsin accepted the twins, they intended to take out loans and earn scholarships. Alyssa went into a Wisconsin homeschooling program so she could work more hours. Jerad drove a truck for $12 an hour, which disqualified the family for grocery assistance. Matt Wopat hit his three-year anniversary of commuting between Janesville and Indiana. Five years after the plant closure, Mike and Barb Vaughn clawed their way back almost to the income they had enjoyed before. Barb thought losing her job at Lear was a blessing. After years of study and struggle, she loved helping disabled adults achieve independence.

Almost five years in, more than half of Janesville residents remained worse off. Fully 60% believed the town would never recover. Despite creating almost 2,000 jobs, the town still had a shortfall of 4,500 fewer positions than when GM closed in 2008. Finally, in late 2015, GM announced that the Janesville plant was permanently closed. By 2016, local unemployment fell to under 4%, but the new jobs pay far less than the salaries people once earned at GM.

About the Author

Journalist Amy Goldstein of The Washington Post is a Pulitzer Prize winner and a former fellow at Harvard University and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She immersed herself in the affairs of Janesville, Wisconsin, for five years prior to writing this book, which was listed among 2017’s best books of the year by the Financial Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, NPR, the Wall Street Journal and the Economist.